RESEARCHERS believe they have solved the riddle of why prostate cancer spreads in some men but not others.

And it could lead to new treatments that stop tumour cells advancing round the body – potentially saving many more lives.

In most cases, when a man is diagnosed with prostate cancer, it is still confined to the prostate gland itself and has not migrated elsewhere.

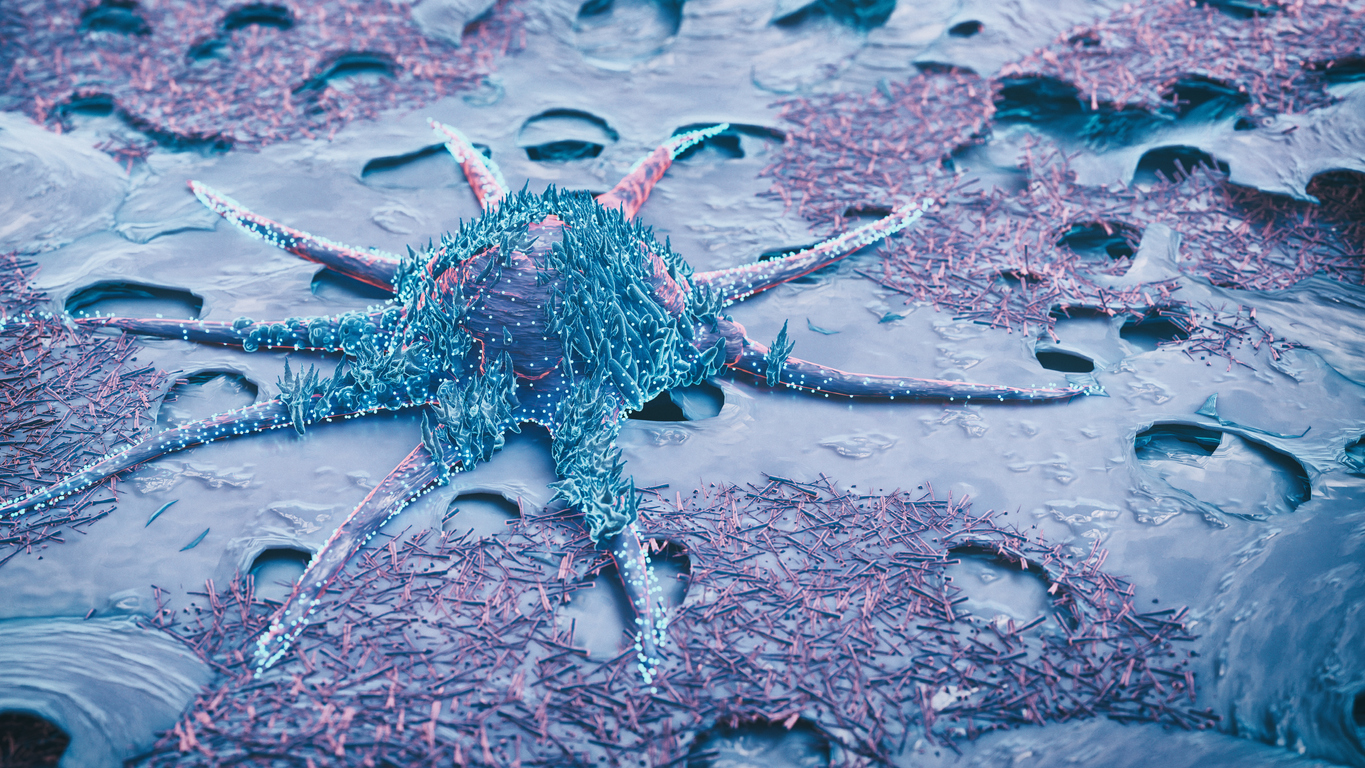

But for roughly one in five men, cancerous cells have already travelled out of the prostate and into other organs and tissues.

This process – called metastasis – means survival prospects are generally much poorer.

Now a team of experts at the Medical University of Vienna, Austria, have uncovered vital clues to how the process works and, potentially, how to stop it.

Their research, published in the journal Molecular Cancer, identifies changes in a specific protein in cells that seem to kick-start metastasis in prostate cancer.

Called KMT2C, this protein normally helps regulate certain processes in different types of cells in the body.

But when it experiences slight mutations, KMT2C seems to lose this ability to regulate those normal processes.

This, in turn, encourages greater activity in a known cancer gene – called MYC – which then prompts healthy cells to start dividing at a rapid rate, driving both the growth and the spread of cancer.

The discovery not only sheds light on what makes prostate cancer spread but raises the prospect that it could be stopped or prevented.

KMT2C mutation can be detected via a blood test, which means doctors may soon be able to identify men who are at most risk of their cancer spreading, allowing them to modify treatment plans to give the best chance of keeping tumours in check.

In addition, drugs called MYC inhibitors – which block the effects of the cancer-prompting gene – are currently undergoing trials and could be a powerful new treatment against advanced prostate cancer in the next few years.

Professor Lukas Kenner, an expert in pathology who led this research, said that the same underlying causes are often found in other cases of advanced cancer.

‘A high level of KMT2C mutation characterises many types of cancer, such as breast, lung, colorectal, bladder and even skin cancer,’ he said.

‘Our study results have a great deal of potential in the research, diagnosis and treatment of malignant cancers in general.’